Why Some Boats Are Honored and Others Are Not

The term “honored” is used here as short hand for “preserved,” “conserved,” “replicated” and given special status for being “of historical importance.”

The two traditional gaff rigged boats discussed below appear as examples of historical importance. They are, coincidentally, both scows, but their importance comes not from being scows but from what being scows enabled them to accomplish in their long careers. Those accomplishments, in my opinion, are part of the reason that they are worthy of being honored. Those accomplishments continue, in new ways, in the present day.

My last post (see Butt Head Schooners…March, 2022) dealt with two boats, both in Texas and both of demonstrable historic value and importance, that have not been honored, for reasons that are either unstated or unknown.

After a discussion of the first two boats, one from the USA, the other from New Zealand, I want to offer some ideas about the sometimes obscure and always complicated processes of maritime historic preservation.

ALMA

ALMA is a gaff rigged, top sail scow schooner built in San Francisco, CA in 1891. She is a designated National Historic Landmark and is owned and operated by the San Francisco Maritime National Historic Park (US National Park Service).

[From here on I will use the term “Frisco” when referring to the city and region of San Francisco, a city that is, or used to be, very special. Having grown up in California I am weary of the pompous use of the term “The City” when referring to Frisco. “The City” is used by vapid, virtue-signaling Yuppies with no sense of history, or style. “Frisco” says it all.]

Alma is the last of almost 200 scow schooners that worked the waters of San Francisco Bay on a daily basis. She is not unique except for the fact of being the sole survivor of her type—in Frisco.

Her length is 59 feet on deck, 80 feet overall (LOA), including bowsprit. Her beam is 22.6 feet and her rig, as stated above, is that of a gaff topsail schooner.

Her draft is just 4 feet, shallow for a 60 foot long schooner, and it is her hull, draft and rig that combined to make her so well suited to her job over 130 years.

Her hull is shaped like a cigar box; her bow has a scow’s angled up-tilt, similar to a jon boat and is almost as wide as her beam.

Alma’s deck is flat—no camber—her bottom is flat and heavily planked. She uses lee boards for lateral resistance and very probably goes to windward “like a cow in a bog.” No matter, she runs before the wind and reaches across the wind like a lady, and that is what enabled her to do her jobs.

Alma has been in San Francisco Bay, which is really a series of connected bays, for all of her life. As you can see in Photo #1 she isn’t a clipper ship or a sea-going trading schooner sailing to Hong Kong, Alaska or South Australia. She is not romantic or lofty; she is practical, useful and adaptable to circumstances.

San Francisco Bay, Alma’s home waters, is composed of a series of bays which, when taken together because they are all connected and all of their waters eventually flow into the Pacific Ocean through the Golden Gate straits, form an estuarine system of 160 square miles, 60 miles long when measured North to South. This makes the Frisco bay system the largest Pacific estuary in the Americas, meaning the entire Western Hemisphere.

The water is shallow and was made even more so by the deposit of vast amounts of sediment deposited in the 19th century by hydraulic gold mining operations.

The tidal range, on average, is 5.8 feet—significant—especially with even higher tides associated with the full moon.

The entire estuarine system has three straits; narrow, constricted passages caused by large rock outcroppings that cause narrow bottlenecks. The combined effect of tidal currents choked down into narrow straits, frequently creates current speeds up to 7 miles per hour (that’s 7 statute miles per hour, not nautical miles). 7mph can feel pretty fast when you are fully loaded with logs stacked head high on deck with the rocks rushing by.

Today the many miles of shoreline in the surrounding the 1600 square miles of estuary have a network of roads to facilitate the transport of goods and people. In Alma’s day there were very few roads, so the scow schooners carried almost everything needed and used in Frisco and a few other towns on the bay, like Petaluma.

Here are two examples of Alma’s work:

From 1926 to 1957 Alma hauled oyster shell, dredged up in the bay from ancient oyster reefs. She carried between 110 tons and 125 tons of shell, each week, up the Petaluma river, to Petaluma, NW of Frisco. The shell was a necessary ingredient for the manufacture of chicken feed. Petaluma has long been the “chicken capital” of California. [Note that even in the relatively modern times of 1926 to 1957 the transport of low value but necessary items, like oyster shell, was more cheaply done by water transport rather than by truck.]

Frisco, like most other Americans cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ran on horse power. And horses ran on hay.

When trying to imagine what the scale of horsepower was like, think about where you live today and also think about whatever larger town or city may be nearby.

Imagine that all the cars, trucks, buses, taxi cabs, semi trucks and trailers, motorcycles, golf carts, delivery vans, postal vans, moving vans and beer delivery trucks were replaced with horses and horse-drawn wagons, carriages, trolley cars, etc. Beer delivery wagons are always a useful metric, especially in Frisco.

All the horses were kept in stables in town. They needed to be close to where they worked each day. In order to do this they had to be fed hay, every day. In Frisco the hay came from riparian meadows located in the delta of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers—up to the NE of Frisco—past the Carquinez Strait and about as far from Frisco as you could go by boat and still be in “the Bay.”

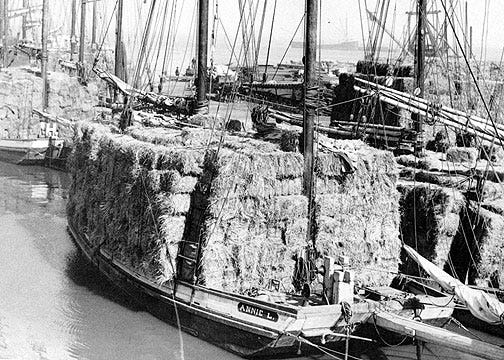

Alma and her sister scows were the perfect vessels for hauling hay, with wide decks, flat bottoms, and wonderfully stable under sail. Their shoal draft and lee boards gave them access to the shallow waters of the Delta.

The tides were, potentially, also a big help, as they were and still are in England, Holland and France. If you paid close attention to the tides you could use the energy of the tide to help propel your vessel, together with the wind in your sails, up the Bay on the flood tide and back down on the ebb, with the deck stacked high with bales of hay. See Photo #2 below:

When the deck was stacked high with hay, or anything else, the sails would be reefed in order to raise the booms above the level of the cargo. (Please remember that reefing without a big deck cargo was the norm; with it, the head of the sail was brought downward, the boom stayed in its normal position and sail area was reduced incrementally according to wind velocity. This scow technique had nothing to do with wind velocity and everything to do with continuing to effectively sail even with the deck stacked high with cargo.) Flying a topsail above the reefed mainsail increased the sail power available. This is a small, useful example of being in harmony with the forces of the Natural World; moving bulky, heavy cargoes without the use of fossil fuel—or any other type of fuel—just using the wind and the tide.

Back in Frisco the hay would be unloaded and hauled away for sale and distribution—by horses.

Alma is still sailing in Frisco today, where she is cared for and honored by the National Park Service, taking passengers for tours on the bay, under sail, through the sunshine and the fog. (See video: Alma Sails, Steven Fisher Productions). You will see passengers and crew on the Alma, the volunteer crew doing the same jobs done by other crews over the past 100 years. Call this “living history” or call it “experiencing the realities of the past’.

(Also check out this video: BAADS on Scow Schooner Alma.) This is of special interest to me. BAADS is the acronym for Bay Area Association of Disabled Sailors.

They look comfortable and seem to radiate happiness. I find it fascinating and reassuring that Alma’s wide, flat deck and wide, stable hull are, by pure coincidence, exactly the right conditions needed by people using wheel chairs, crutches, prosthetics and service dogs.

This is Serendipity made manifest—on a traditional sailing vessel. HONORABLE INDEED !

JANE GIFFORD

The Jane Gifford, see Photo #3 above, is a gaff rigged topsail ketch, flying 3 foresails. She is also a scow, built in Warkworth, New Zealand in 1908. Scows, as a boat type, were just as popular and well-suited in New Zealand as they were in Frisco.

Jane Gifford’s builder named her after the ship his ancestors came to New Zealand in, back in 1842, a barque named Jane Gifford. It seems he had a strong sense of history-and honor.

After working for decades in Auckland and other areas of New Zealand the scow came back to Warkworth, where she was eventually bought by the Jane Gifford Restoration Trust, extensively re-built, and re-launched in 2009.

She is about the same length as Alma, but 3.5 feet less in beam; her hull is a little more streamlined, less of a cigar box than Alma and her bows are up-swept and “shippy”.

130 sailing scows were built in New Zealand between 1873 and 1935. They were popular because they could navigate narrow tidal estuaries and, like the Frisco scows (and Thames sailing barges), they could rest upright on their flat bottoms when the tide was out. This simple but important feature made them easier to load and unload.

From 1921 to 1938 Jane Gifford, also like Alma, hauled sea shells, mined from reefs, to cement factory on Warkworth.

Video #3: The “Jane Gifford”—Warkworth, NZ

As you watch Video #3 above, look closely at the seams of her topsides, shown in photographs taken before her latest re-build. The planks, fastened horizontally on her frames, are curved downwards, not intentionally by any builders or shipwright but caused by years of stress, resulting from heavy loads, constant motion while underway and the inherent elasticity of wood.

She was “hogged,” and badly so but the most recent re-build took care of all that damage.

It is impressive to see how much stress must have been exerted to cause that damage and equally impressive to see how well, how honorably, she stood up to it.

Video #3 expresses better than I can just how beloved and important Jane Gifford is to the community of Warkworth and to New Zealand as a whole.

A COMPARISON

Alma and Jane Gifford are both sole survivors of their type in their home waters.

Both were used to haul low value, high bulk cargo:

Hay, a sustainable energy source based on sunlight that when re-cycled through the gut of a horse or a cow has value as organic fertilizer.

Lumber/timber, paving stones, bricks, and shell, all used in cement for building and in infrastructure.

Both are still sailing in their home waters carrying passengers.

Both are restored and maintained; Alma with public funds, Jane Gifford with private funds.

Both are examples of the past, representing historic uses, energy forms and methods—all giving us a basis for comparison i.e., teachable moments and an appreciation of how far we have come and at what cost.

So, given these factors and circumstances that the two boats share, what conclusions, if any, might be drawn about similar vessels with similar histories in similar circumstances—especially when these vessels are not and will probably never be honored?

HOW DO WE DECIDE WHICH BOATS TO HONOR?

I have given this question a lot of thought lately. What I have come up with, so far, is just a list, a preliminary stab at organizing information to facilitate critical thinking about the factors, circumstances and requirements—as well as the many hazards/challenges that surround the preservation of historic vessels.

As usual in this space, I am stating my opinion and mine alone, based on observation, study, some experience and a deep appreciation of traditional sail, especially working sail.

FACTORS, CIRCUMSTANCES and REQUIREMENTS

To think about as you carefully sand her topsides.

HISTORIC USE. (By specific boat or type of boat), especially the connection of that use to a particular location, town or region, where that vessel and others like her were used.

RECOGNITION OF VALUE. Value has many forms:

Value as part of the history, the “story” of a particular place’

Value as a cultural icon, meaningful to people, especially local people.

Value as a tourist attraction, as the “flagship” attraction for the waterfront.

Value as platform for teaching and learning-not always the same thing

CLEAR SENSE OF PURPOSE—by individuals or organizations clearly focused on historic preservation. (The National Park Service or the J G Restoration Trust.)

What is it, exactly, that the organization wants to honor?

Is it a particular vessel, a type of vessels particular activity, i.e., the occupation of the vessel ex. warfare, exploration, fishing, trade?

It is crucial that the goals/mission of the effort be seriously considered, discussed, agreed upon and articulated. Ad Hoc doesn’t do it.

LEADERSHIP. This is also crucial, but sometimes elusive. Leaders arise but they also go away, for a number of reasons; death, illness, divorce, money, scandal, re-location, etc. This is where and why and how an iron-clad mission statement is of great value—an anchor to windward when the storm winds blow. (See Continuity below).

FINANCING

Expenses—Maintenance, Repairs, Insurance, Slip fees, Public Relations, etc.

Possible Income Sources—Endowments, Sponsors, Grants, Pledges/Donations, Earnings, etc.

Can the vessel earn enough income to cover Expenses?

Or is she supported by and dependent upon fund raising?

COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT. The relationship between the boat and the community can be mutually beneficial if the boat proves itself to be a steady attraction and if the community leaders are willing to adhere to the mission of the preservation group. This is where you start to become aware of the intersection of leadership, financing and continuity. Also, and of great, proven value, are the efforts of competent, multi-tasking women with impressive networking and organizational skills. Where would our society be without them?

LOCATION. Where will the boat be kept? On land, as a static display? Or in the water? Does the organization want to sail her, with passengers? If so, then dock space, parking, bath rooms and disabled access are all needed. And costly.

Can USCG safety regulations be met?

Can reliable crew be found and trained?

Will her presence contribute to the local waterfront as a tourist attraction?

If so, can this be done without bastardizing her into some ridiculous theme park “pirate ship”? (Remember, different people see and understand historic sailing vessels in different ways.)

CONTINUITY. Time passes; she may be the jewel in the crown of the preservation organization today, but what will she be 10 years in the future?

Will she still be relevant?

Will she still be seen to be relevant?

Can her owner/operator be creative on a constant basis?

COST vs. BENEFIT. Such a basic concept with useful criteria to guide decision making. Its importance should be self-evident and hardly worthy of comment. However, in my own experience I am aware of three maritime preservation organizations that self-identify as “maritime museums” that have accepted small historic vessels as gifts and then let them rot away, in front of the public, for lack of several of the factors and circumstances listed above, the principle ones in each case being Financing, Recognition of Value, Leadership and Clear Sense of Purpose.

A few meetings of the Board of Directors, focused on the balance between Cost and Benefit, would have revealed that there was not adequate funding and that knowledge and ability were both lacking. In short, Costs far outweighed Benefits and a simple refusal to accept the vessels as gifts—unless accompanied by funding—would have avoided embarrassment, shame and the death sentence to the boats themselves.

In closing I want to return to the basic, core question of WHY? Why is it important to preserve these complex, arcane objects known as traditional sailing vessels?

What’s the fuss all about?

Our planet has 70% of its surface covered by water. As humans evolved they were confronted, in most places, with the need and utility of going out on the water to obtain food and to go to other places. They learned how to build the boats necessary for fishing, food gathering and travel. The rest is history, just ask the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Boats are in our DNA.

Sailing, on all boats and on all waters of our planet is an almost magical act; quiet, powerful movement created by the combination of sails and wind, not the blasting roar of fossil fuel powered engines.

Paradoxically, we are now at a point in our culture and society where there is great and growing interest in “alternative forms” of energy, a term that accidentally reveals the ignorance of the fact that current energy forms, i.e., fossil fuels, were once themselves thought to be “alternative forms.”

Wind power can be effectively used without having to be captured by turbines in order to make electricity that then needs to be transported by power grids and “stored” in banks of batteries.

Wind is an original and unique, primal source of energy. As it passes over the sails, propelling your boat, it goes on, without cables, batteries or the slaughter of thousands of birds, to also propel the other boats around you.

Wind is ever-present and inexhaustible- sailing vessels have been using it for centuries. Sailing vessels are the exemplars of humans’ ability to harmonize with the Natural World, especially meaningful in the present time when such examples seem to be increasingly scarce.

This harmonious, creative use of basic wind power by means of sails is still with us, all around the planet and it behooves unto understand its history and relevance.

This is why I say that understanding, using and preserving traditional sailing vessels is important.

They have a lot to teach us, probably even more to teach our children and grandchildren, and THEY ARE IN OUR DNA!

PAU

Duncan Blair

As always, all questions, complaints or opinions are welcome.