In 1928 the four-masted schooner Chiquimula left the port city of Santo Domingo, on the southern coast of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, loaded with a cargo of goat manure to be delivered to Tampa, Florida.

This post, the first of two parts, is offered as an exercise in understanding how and why this high-volume, low value cargo, similar to many other cargoes, was assembled, organized, loaded transported and delivered.

The purpose of the exercise is to creatively think through the series of actions needed to to get cargoes gathered, loaded, transported and delivered 100 years ago by commercial sailing vessels.

In order to attempt this it is necessary to make a series of assumptions—call them guesses—about the actions taken and the types of energy that were used.

All the assumptions/guesses are mine. Please feel free to question them and to offer your own ideas; doing that will make the exercise much more interesting.

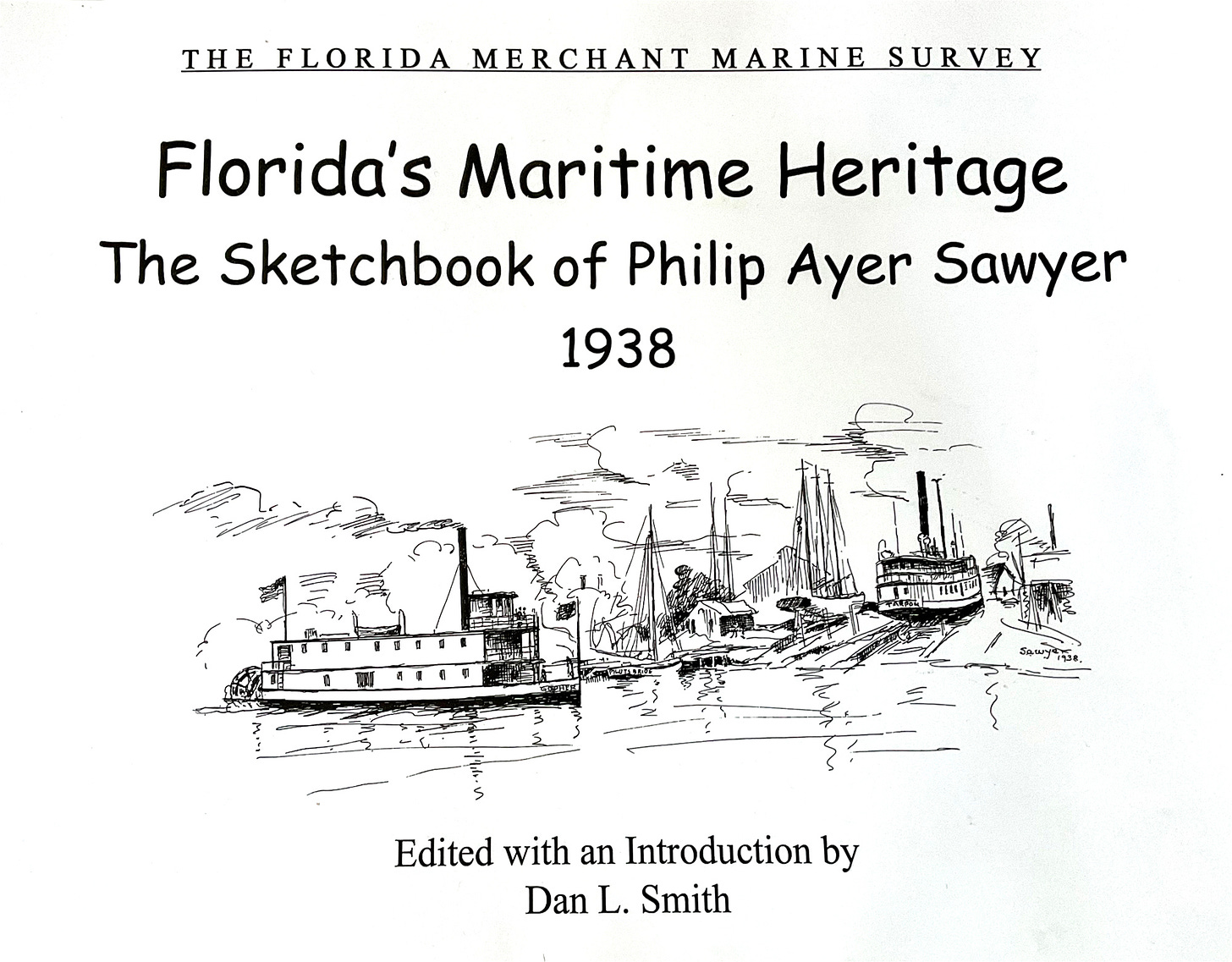

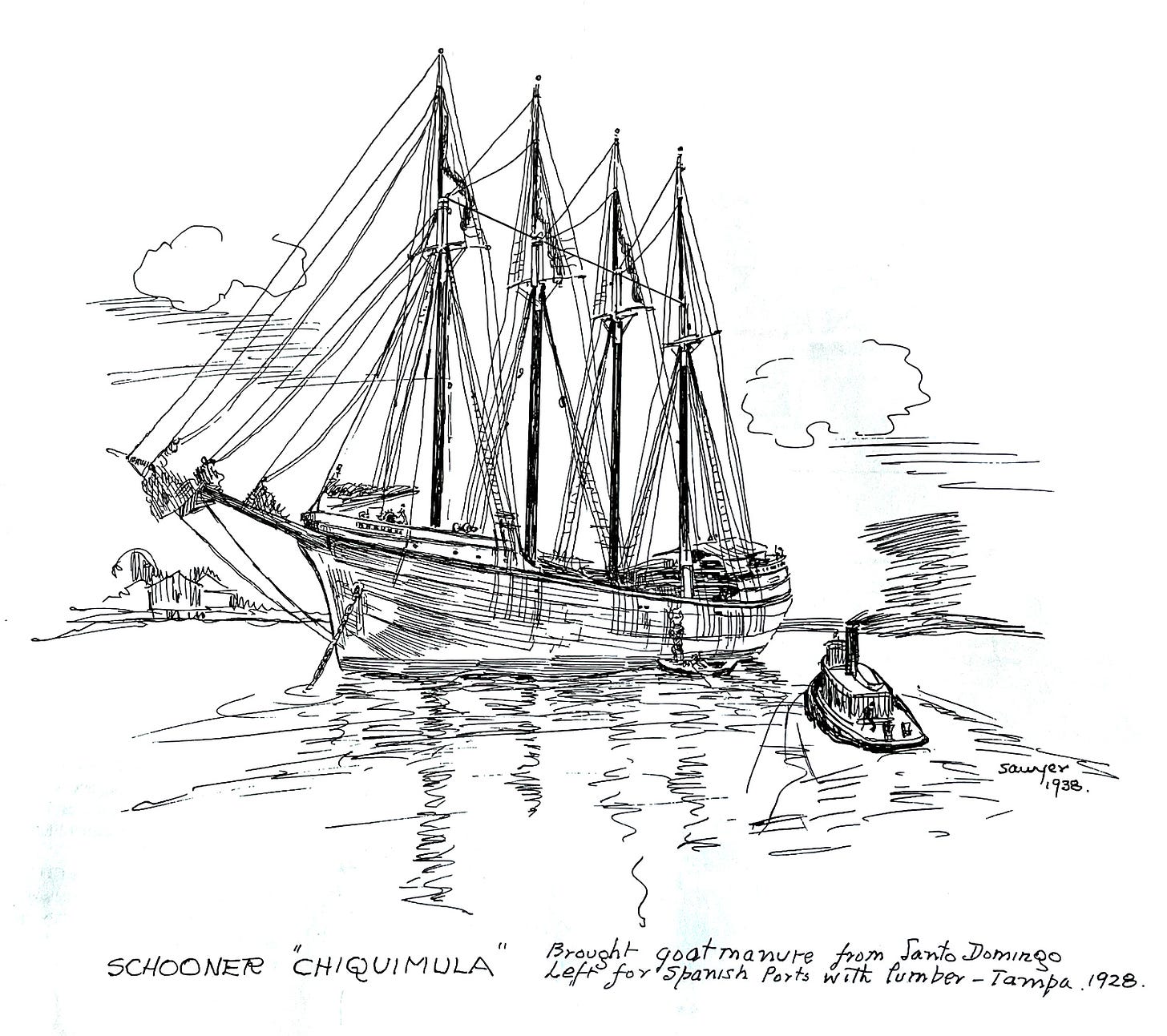

Maritime historians seem to agree that in the second half of the 19th century American shipyards began to build schooners of greater length and consequently, more masts, than had ever been built before. These were not the small, agile schooners of the coasting trade; they had 3 or 4 or even 5 masts. Chiquimula was one of these bigger schooners, clearly not a nimble coaster or even a Gloucester fishing schooner.

I will assume that Chiquimula was designed and built to carry several hundred tons of cargo and that, in order to load and unload that cargo, she was equipped with one or more “donkey” engines—still powered by steam in 1928.

Donkey engines, so-called because they were relatively small, powerful and dependable, were used on large sailing vessels to load and unload cargo, to raise the very large sails, to operate the bilge pumps and, when necessary, to haul up anchors.

So, just how was the goat manure gathered, assembled and packaged on a scale large enough to fill the cargo hold of a large schooner?

My guess is that it may have come about something like this: when “the Market” signaled that there was a demand for organic fertilizer it was seen that goat manure, already in the form of pellets met that demand, and that it could be sold profitably in Florida, specifically Tampa.

Then, individual campesinos organized their families and friends and their employees, if they had them, to go out, gather the goat manure and put it into bags.

These bags would have been cheaply made and coarsely woven, similar to the burlap bags still used in the U.S. oyster fishery.

The bags would have probably been a standard size, shape and quality so as to contain a uniform quantity and weight of the goat pellets. If they were weighed that could easily be done with a simple balance beam hung from a tree.

Once uniform bags of pellets had been gathered, horse-drawn wagons or ox carts could be loaded, by hand, and the bags consolidated in a warehouse or even a dockside storage shed.

Once on the dock in Santo Domingo the bags could be placed, again by hand, into cargo nets, hoisted up by cargo booms with a block and tackle powered by a steam donkey, swung on board the Chiquimula and lowered down into her cargo holds where they would be removed by hand, from the nets and securely stacked, by hand!

Because Santo Domingo is on the southern coast of Hispaniola, my guess is that, once she was loaded, the schooner would be maneuvered away from the dock by a steam-powered tugboat and towed out of the harbor. (See Illustration #2 above, Sawyer’s sketch of Chiquimula with tug boat alongside.)

After dropping the tow line Chiquimula would probably go South West to “make her offing”, then head North West, past Jamaica and Cuba, then up through the Yucatan Channel into the Gulf of Mexico.

[Please try to make the effort to look at a map of the Caribbean as you read this in order to better visualize and fully understand the geography. Maps are valuable].

Once into the Gulf of Mexico she could, at some point, turn to Starboard, going East, and reach Tampa. Arriving there she would probably have called for a pilot and a steam tug, to safely get her into the harbor and alongside a dock.

Her steam donkey(s) would be used again to hoist the cargo net loads of goat pellets up and out of the cargo holds and place them on the dock. From there the goat manure would be hauled away by trains, pulled by steam engines. (Railroads arrived in Tampa in the late 1880s).

My best and only guess is that the goat manure was used to fertilize citrus and/or vegetables.

The caption of Sawyer’s drawing states that after discharging her cargo inTampa, Chiquimula loaded a cargo of lumber which she hauled across the Atlantic to “several ports in Spain”.

The next and final post about Chiquimula, entitled The Chiquimula Saga Part II, will address the various forms of energy used to get the cargo from the countryside of Hispaniola to the orange groves and truck farms of Florida.

I will also attempt to offer some ideas and observations about the possible relevance of Chiquimula example to contemporary sail cargo operations. STAY TUNED.

PAU

As always, all comments and ideas stated above are mine alone.

Duncan Blair

References:

Florida’s Maritime Heritage: The Sketchbook of Philip Ayer Sawyer, 1938. The Florida Merchant Marine Survey. Florida Historical Press, 2010

Steam Donkey, Wikipedia