The Apalachicola Oyster Sloop

I now live in Apalachicola, Florida, a place my wife and I have visited over the years and often returned to. I like it here; the weather is great, the people are interesting, and there is a lot of history and character to the town.

The claim that Apalachicola is “The Oyster Capital of the World” is posted on signs and T-shirts all over the town.

I think this claim is both ridiculous and false. What I have learned is that for many decades, 90% of all the oysters consumed in Florida came from Apalachicola Bay. That in itself is a significant achievement and is one that was enabled by, and depended upon, a particular type of boat, the Apalachicola Oyster Sloop.

Unfortunately, today the oysters are gone. The sail-powered oyster sloops left long ago.

The oysters consumed today in local restaurants and raw bars come from other places: Cedar Key, Texas, and Louisiana. A few are raised in an aquaculture operation a few miles west of Apalach.

A cascade of misfortune, both ecological and social, some of it avoidable, has caused oystering in Apalachicola Bay to cease. The government-mandated closure began a few years ago and may possibly end—or not—in 2025. It depends.

Ten days ago I ran across a 2024 calendar entitled “Apalachicola—Oyster Capital of the World”. It caught my eye because of the period photographs of downtown Apalachicola and sailing oyster sloops.

I had already run across some of the photographs in my own research, but several were unknown to me. The photographs were accompanied by brief, informative, and useful captions.

The calendar was created by a local man named Charlie Sawyer, who is a graphic designer and restorer of old photographs. I called him after studying the calendar’s information, and he graciously gave me permission to use the photos in this blog. Most of the photos shown here are ones that he discovered in the State Archives of Florida, some of which he restored.

The calendar is entitled A Photographic History of Oystering on the Forgotten Coast, 2024 Wall Calendar. (See References below for contact information.)

This discovery was especially fortunate for me because the calendar has several photos of oyster sloops that were bigger than the ones I was aware of.

PHOTOS FOR THE MONTHS OF FEBRUARY AND APRIL, 2024.

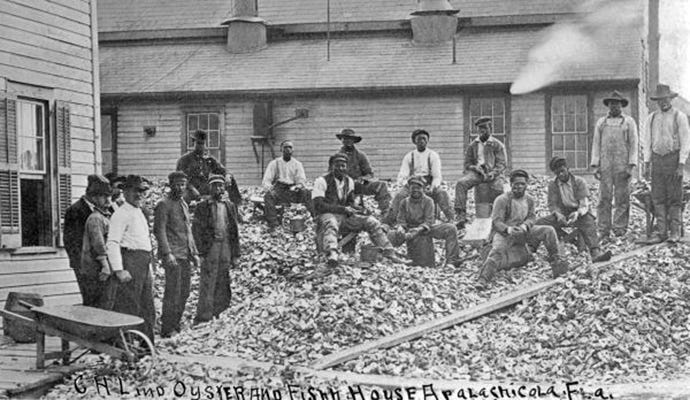

These photos depict an oyster processing yard in Apalachicola with huge piles of oyster shells that graphically show the scale of oystering in Apalach from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries.

Oysters were definitely not manufactured, but they were shucked (removed from their shells, by hand) and then pasteurized and canned. The photos reveal the scale of the processing operations. They also tell how a German immigrant, Herman Ruge, became “Florida’s most successful seafood processor.”

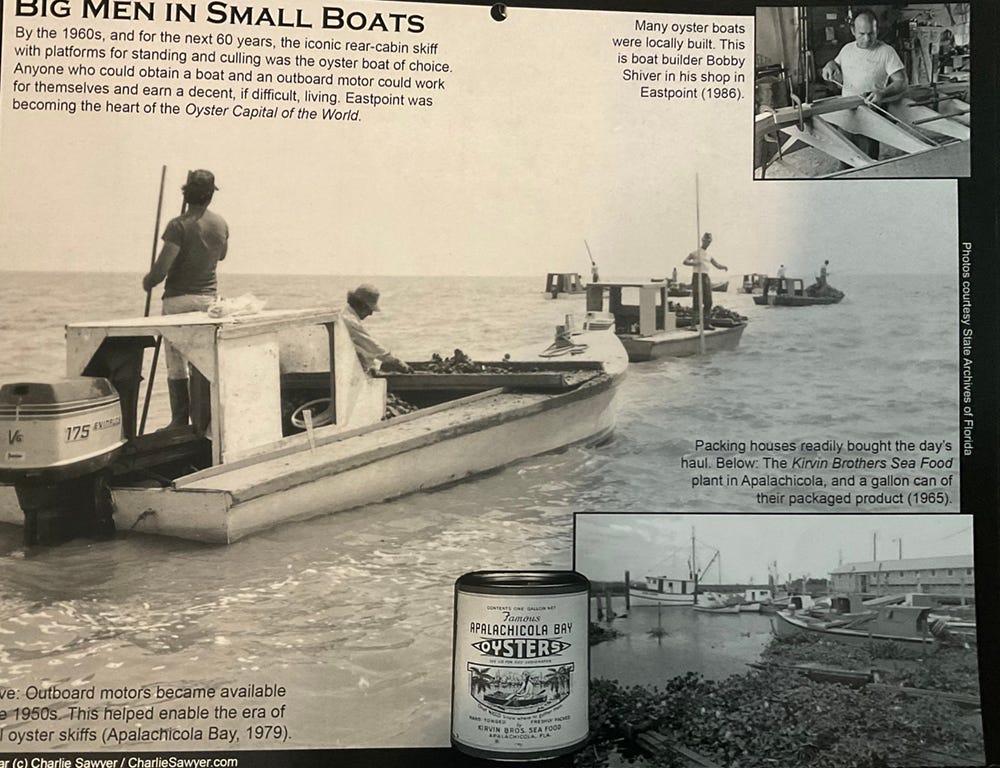

The calendar photos for August, 2024, show the Kirin Brothers seafood plant in 1965, along with an image of a one gallon can of Kirin Brothers’ oysters. All of this was made possible by Herman Ruge, Louis Pasteur and the un-named hundreds of local people, both Black and White, who built the oyster sloops, harvested, hauled, shucked and canned the oysters.

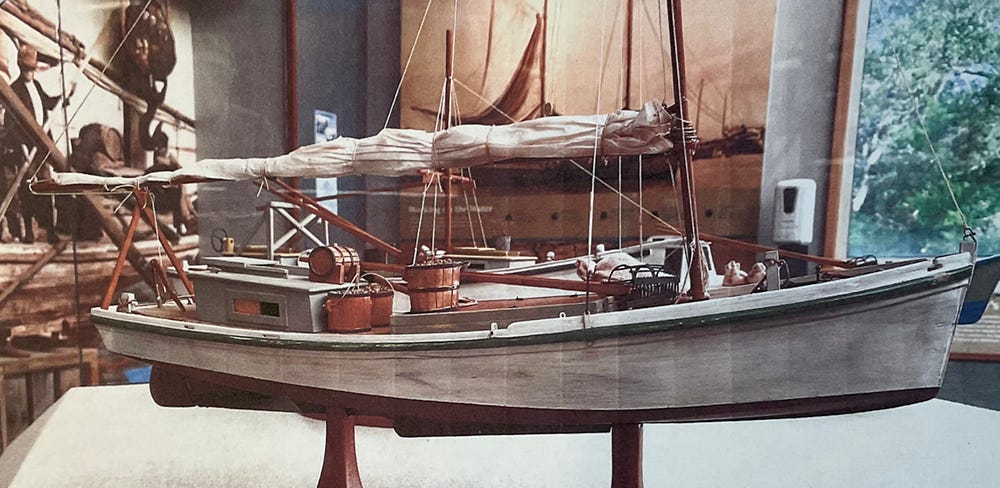

This photo of a sailing Apalachicola oyster sloop (below), dated 1890, appears to have been taken dockside in Apalachicola.

The sloop is clearly gaff rigged; the photo shows a peak halyard, gaff and mast hoops. The boom, resting on a scissor crutch, is impressively long, an indication of the size and power of the sail. I repeat the caption here because it is an especially powerful and concise statement about working sail.

Caption: “From the mid-19th century, and well into the 20th, wind power was the only practical way to get a large boat and its crew onto the oyster beds.”

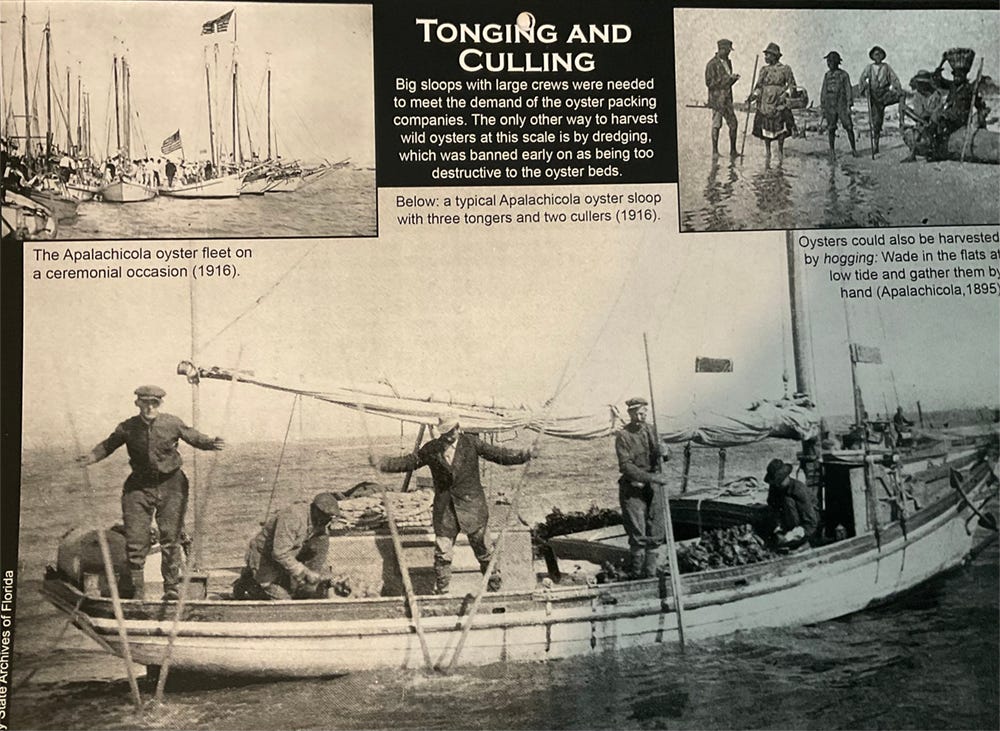

The caption reads “a typical Apalachicola oyster sloop with three tongers and two cullers (1916).”

This boat looks be considerably larger than the boat depicted by the John Ficklen model in Photo #1 above. It also seems to have a shorter boom and a foresail with a bowsprit.

A second photo from May, 2024, in the upper left hand corner shows “The Apalachicola oyster fleet on a ceremonial occasion (1916).” In this photo all the boats that are clearly seen have bowsprits. More on this in Part Two.

Tongers.

The tongers in the May photo are using standard oyster tongs, having 10-foot-long handles capable of reaching down onto most of the oyster reefs in Apalachicola Bay.

Each of the two handles ends in a roe of 3–4 inch long iron teeth, much like a heavy-duty garden rake. The teeth interlock when brought together by the handles, which are manipulated by the tonger. This enables the tonger to reach down into the water, feel the oysters, close the teeth around the oysters and bring them up to the deck of the sloop, hand over hand. Once on deck, the tongs are opened, releasing the oysters onto the thwart-ships culling board.

Cullers.

The cullers handle each oyster or clump of oysters, knocking off calcified debris with a short iron bar. Immature oysters are thrown back into the water. The work of the cullers is important. They clean up and organize the oysters brought up by the tongers. Oysters are and were sold by weight, so the culling process serves to give a true weight by removing anything that is not an oyster.

Tonging vs. Dredging.

The center photo for May, 2024, mentions”big sloops with large crews.” It goes on to say that dredging was “the only other way to harvest wild oysters at this scale.”

Oyster dredges are heavy, box-like rectangular frames made of iron. One side is open, with large teeth attached along the long edge, that are designed to dig into the bottom sediment and dislodge any oysters.

In doing this the dredge systematically disturbs and destroys the matrix of rock, coral and old oyster shells that the healthy oysters are attached to. The sideways, nearly horizontal dragging of the dredge destroys the critically important oyster habitat offered by the matrix.

Conversely, the tonging is almost completely vertical; the tonger feels along the bottom until he finds oysters, then grabs them, plucks them with the teeth of the tongs and pulls the tongs straight up through the water column, leaving the matrix largely undamaged.

“Dredging was banned early on as being too destructive of the oyster beds.”

The fishery regulators got it right that time with their ban on dredging.

A Final Note on Oyster Sloop Size.

The photos for the month of June, 2024 show a small photo, top center, of a gaff sloop with the low topsides and up-swept bow and sheer line of the oyster sloops. This boat has seven men shown on deck; two standing on the cabin roof while the other five are standing on a huge pile of oysters, which is described as “... a full load of seed oysters ready to be broadcast upon our seed beds.” c.1920.

Seed oysters, sometimes called “spat”, are the larvae of oysters that have attached themselves to empty oyster shells on the bottom. Today, as in 1920, they reflect the “hand of man”, in this case aquaculture. This may be evidence that by 1920 the demand for oysters was beginning to exceed the supply. It may also just be evidence of Popham’s questionable business practices.

I am only interested in the photo because of the size and design of the sloop. It may be another data point. The story of William Popham I will leave to you.

To summarize, we have a high value product—oysters—for which there begins to be a considerable and constant demand. With the addition of Pasteurization, canning, and a railroad line to Apalachicola, the processing, packing, and shipping functions were all covered.

The actual harvesting of the oysters, along with the shucking and processing, provided employment, even through the hard times of the Great Depression, to local men and women in Apalach. Boat builders were also kept busy, proof once again that, almost always, everything is connected to everything else.

The Apalachicola Oyster Sloop, which I am beginning to think may well be considered to be a genuine vernacular boat type, was the sailing vessel that was developed to tong oysters.

I repeat the caption for March, 2024, because it is well worth emphasizing, “From the mid-19th century and well into the 20th, wind power was the only practical way to get a large boat and its crew onto the oyster beds.”

It is worth noting that the oyster sloops, once they were heavily loaded with oysters, also hauled their loads across Apalachicola Bay and delivered their cargo of oysters to the canneries, all done using wind power.

I plan to continue my “shade tree” forensic analysis of the Apalachicola Oyster Sloop and its relevance, in a second post, scheduled for early December. Like this post, it will also be FREE.

PAU

As always, all ideas and opinions are mine alone.

DUNCAN BLAIR

REFERENCES:

Photo #1, by Duncan Blair. A very detailed and accurate model of an Apalach oyster sloop on display at the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (ANERR), East Point, Florida. Model made by John Ficklen, deceased.

More on this and its importance in Part Two.

All Other Photos: State Archives of Florida, reproduced and restored in “ A Photographic History of Oystering on the Forgotten Coast” a Wall Calendar by Charlie Sawyer.

Charlie Sawyer contact info: charlie@CharlieSawyer.com

My sincere thanks to Charlie Sawyer for helping a stranger on the telephone. DKB