In 1986 divers in Florida discovered the remains of a dugout canoe, inland from Daytona. Carbon 14 dating established its age at approximately 5000 years; 3000 years before the birth of Christ and 4,500 years before Columbus came ashore in the New World.

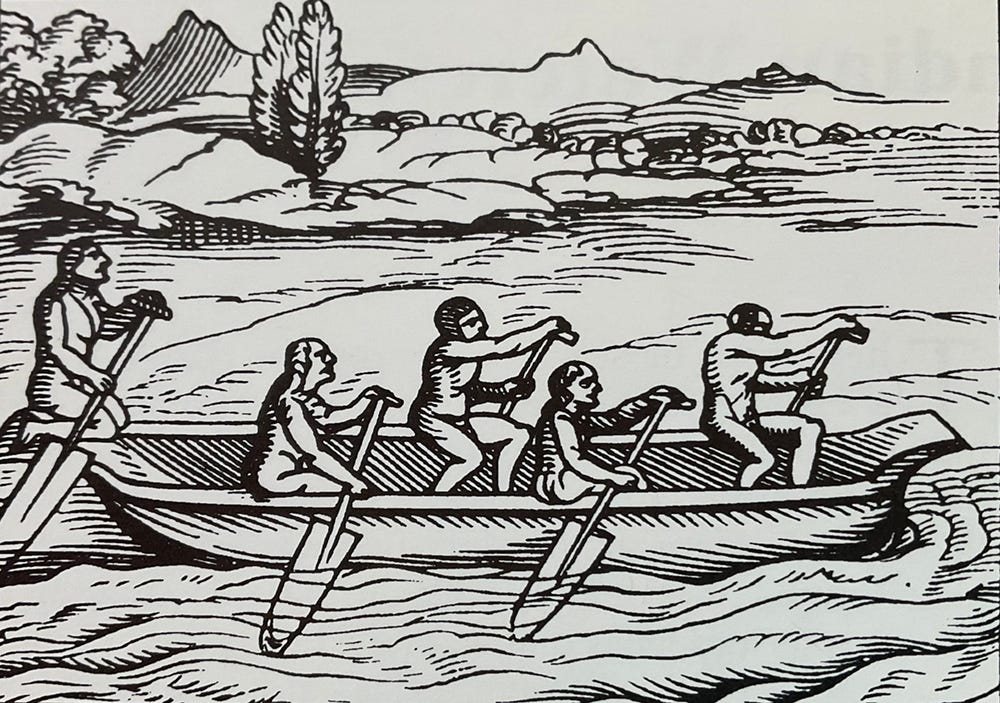

On his second day in the “New” World, Columbus’ journal recorded natives coming out to his ship in “watercraft wonderfully shaped in the way of this land,” some of which were capable of carrying as many as 40 or 50 men. A native, unknown to history, also taught Columbus the Arawak word for the watercraft—“canoa”—what we now call “canoe.”

It is an understatement to say that the importance of dugouts is still mostly under-appreciated. A few archaeologists and marine historians are aware of the important role they played, but most people, both laymen and boat people like fishermen, sailors and yachtsmen, are unaware, and uncaring.

The making of a dugout is pretty simple—conceptually! Find a tree that is wide enough, tall enough and straight enough for your purpose—not too many branches. Cut it down, or burn away its base if you are in the Neolithic era, then using fire, tools and muscle power, burn, hack, gouge, scoop, chisel and shape the inside and outside as you wish. What you will have when finished is a long, narrow, heavy canoe that can be poled, paddled or even sailed. (I will go into sailing later). The bow and stern can be left blunt, unshaped, or they can be carefully shaped into what are often elegant contours. It is important to leave a considerable amount of wood on the bow and stern since those areas are most prone to splitting and checking because of the exposed end grain.

It is worth noting that dugouts are found across the planet, on rivers, bays, estuaries and swamps—even oceans. They are made from whatever trees are locally available and, like all man-made objects, they not only reflect those who make them, but also are an important part of the material culture of the society that they represent. They are still being made and used. The two photos included in this post are relatively recent. This one taken by me in the 1970s in the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica:

I will argue that the apparent crudeness and simplicity of dugouts, especially very old ones, hides the considerable skill, knowledge and craft of their makers. In the 21st century, we, especially we Americans, have an over-simplified, disdainful idea of Neolithic humans as cartoonish Fred Flintstones, who bang rocks together to make crude tools. I think that the truth is much more complicated and interesting that that.

Neolithic hunters and gatherers had tools and skills that had evolved over centuries, going from flaked edges to ground edges, among other characteristics. The knew how to make tools from bone, teeth, (shark), shell, antlers, stone, woven and twisted fibers, wood and rawhide from animal skins. They know how to use natural, grown curves found in tree branches to make handles that gave the cutting edge the correct “angle of attack.” They “hafted” the cutting, punching, drilling, gouging edged material onto the handles using twisted fibers and/or rawhide which contracts and hardens as it dries. The function of the finished product whether weapon or tool, is easily recognized and understood today.

As mentioned above, the weight and length of the dugouts made them fairly stable. Their length and narrowness make them “track” easily—i.e., go straight—when paddled or poled.And they are wonderfully quiet; no slapping of waves on flat, drum-like, planked bottoms or top sides. This quietness makes them useful for hunting and fishing, especially when using a spear, bow or cast net.

Dugouts were used for warfare—raiding the neighbors—as well as for trading- bartering with the neighbors. Depending on the culture, women sometimes had small dugouts for their own, specific use, used for the gathering of food, medicinal plants, weaving materials, clay for pottery, and firewood.

In 1566 the Spanish Governor of La Florida was visited by Calusa Indians in dugouts, two of which were fastened together by poles and decked over; more space, more stability making them capable of long voyages. The Calusa are known to have traded in Cuba. Tribes on Florida’s Atlantic coast are known to have traded in the Bahamas. The Gulf Stream not withstanding!

Dugouts are what these and other people around the world had, what they knew because they made them and used them on a daily basis, and they used them to good effect.

The two Honduran dugouts in the photo below (taken by my wife in 2014 on Honduras’ Caribbean coast) were made by the Garifuna (Gar-EE-foona). The Garifuna are an ethnic group found scattered along the Caribbean coast of Central America. They continue to make a few dugouts even though the big trees are gone or are too valuable for lumber to be chopped up for canoes.

They make small, 8 to 10 foot dugouts that they call “dories”, and use them intelligently and creatively in an artisanal fishery using free diving with a snorkel, mask and fins to harvest conch (its KONK! not con-shh) and lobster. The dories are carried stacked on the decks of Belizean fishing sloops; traditional, locally built, carvel planked 30 foot sloops with a leg o’mutton mainsail and a small outboard in a well. They are crewed by 5 or 6 men who motor/sail out to the reefs along the eastern coast of Belize and also further East to the Turneffe Islands. Once arrived, they anchor the sloop and 3 or 4 of the fisherman/divers go out on the water, each in his own dory. I don’t know this for certain but I imagine that they each carry water and maybe even a cell phone in a waterproof container; hopefully also a spare paddle.

Each fisherman, while snorkeling, has a light line tied around his waist that connects him to his dory. The water is shallow and the length of the line is greater than the depth of the water.Carrying a mesh bag or a “tickle stick” (a simple 2 foot long wooden stick with a large fish hook on one end), the diver goes down, picks up whatever conchs he saw on the bottom or coral while snorkeling, puts them in his bag and rises to the surface to dump the bag into the dory. Because the diver and the dory are tied together the dory is always near by and easily located. After catching his breath the diver goes down again for more conchs or lobster, using the tickle stick to pull the lobster out from under rocks and coral ledges. Eventually the diver climbs back into the dory; an impressive athletic feat, and paddles back to the sloop to unload his catch, eat, sleep and hang out with the other crewmen. I suspect that cold beer is consumed.

This fishing technique may seem cumbersome or quaint, but I would argue that the free-diving, hands-on approach is safer, in its simplicity, than the mechanical, motorized fishing technology using nets, otter boards or dredges, all of which do extensive, long term damage to both coral reefs and human bodies. The free diving technique also contributes to the sustainability of the fishery by allowing the fisherman to actually see, up close, what he is catching and by doing so avoids the mass, unintended but inevitable killing of unwanted species, a form of collateral damage conveniently dismissed as the “by catch” in mechanized fisheries. Lastly, by using the dories, and the sloops, the Garifuna are keeping an important part of their history and culture alive-and passing it on to the next generation.

EPILOG

There is an amusing, delicious irony in the situation of the Belizean/Garifuna fishermen. Tourists come to Belize from all around the world, spending tens of thousands of dollars and many tons of Carbon pollutants in order to see and to experience what for the fishermen is seasonal work. This includes sailing out to coral reefs where they snorkel in gin-clear water, paddle canoes(made of plastic in colors not present in Nature), while eating fresh fish, conch fritters and drinking cold beer, and lounging on the decks of sailing boats. If you have never eaten conch fritters or conch ceviche you’ve missed out on one of the ocean’s treasures.

SAILING DUGOUTS

I know that dugouts are sailing now in several parts of the world. Just when dugouts began to be sailed is unknowable, I think. I am going to try to dig deeper and will write about this burning question in my next posting.

Finally, archaeology and deductive reasoning, sometimes allies, sometimes not so much, present examples of early humans using log rafts, inflated animal hides, bundles of reeds, etc. to cross water “obstacles” while hunting and gathering. For what its worth I am prepared to say that I believe that the dugout canoe was and is the first “real “boat” to be created by humans. It turned water obstacles into water pathways. Dugouts exemplify human intelligence and problem solving skills, ingenuity and self-reliance. The boat is clearly itself a tool used to creatively meet human needs, desires and local conditions.

Neolithic humans, when blocked by a vast body of water could, as described above, go across it using winds, currents and their own muscles in a boats of their own design and construction; boats big enough to carry people, animals, tools, plants weapons and fire.

This is a concise description of the settlement of the Polynesian Triangle (a 10 million square mile area in the Pacific Ocean) by the Lapita people who originated in Formosa (modern day Taiwan)—all done over several thousands of years by people in boats without any cold beer.

As always, all of the opinions expressed above are mine alone.

Duncan Blair