Since I began this blog I have tried to keep a close eye on my basic goals; the relevance of Traditional Sail (TS) to contemporary life, the lessons contained in and taught by TS that can be applied to our interactions with the Natural World and the potential that TS has as a platform for teaching all sorts of people about energy use, self-reliance, ecology, Earth science, critical thinking, estuaries and resource use, to name a few.

While trying to be true to my goals I also try to have a little fun. I have been married to the same long-suffering, beautiful girl for 45 years and I know that if I can still make her laugh a few times each day that I’m doing all right.

I had originally planned to write about four different skiffs, a small boat style that I am fond of. However, I came to realize that my comments were going to come across as snarky, self-righteous and opinionated—because they were!

I don’t want to do that, most especially not in the context of today’s world. I have come to believe in the importance of making a real effort to think and act positively and so avoid the seductive swamp of complaint and gratuitous criticism.

So I have decided to “think out loud” about just two types of popular skiffs; designs that are so popular and widely used that my critical comments, which I candidly acknowledge, will have absolutely no bearing on their continued popularity. This will be Part 1 of a two-part effort. Part 2, in early January, 2022, will offer some thinking out loud about contemporary designs of traditional small boats and their designers; designs built in both fiberglass and wood that combine the lines and beauty of traditional rigs, hull shapes, sails and even paint colors, with modern materials, technologies and outside-the-box approaches to boat building. Stay tuned for Part 2.

THE JON BOAT

I live in the land of the jon boat. But not the original vernacular version built in a few hours with 1x12-inch planks, a saw, a hammer and a bucket full of 16d galvanized nails. Those are not around any more, they have all rotted away. Too bad, because they were practical, cheap and easy to knock together—like a kid’s sand box.

The current version of the jon boat, see photo #1 above, is available almost everywhere, especially in the South. They are made from aluminum panels with pressed V-shaped ribs for strength and rigidity, and usually have a sheer line reinforced with a tubular metal strip, often containing holes for oarlocks, one on each side.

I, personally, have never, ever seen anyone row a jon boat, but it is possible to do so.

The aluminum panels are fastened with pop rivets. Repairs can easily be made using self-tapping sheet metal screws and silicone caulking, or even Henry’s roofing tar applied with a putty knife. Jon boats come in various lengths in order to accommodate various sizes of outboard motors. They are stable, shoal draft and very practical when used on rivers and lakes, or, when conditions allow, on protected in-shore waters like lagoons or bayous. They are most emphatically not intended for use off shore.

Their simplicity allows them to be easily customized, see photo #2 below.

I think the jon boat, as a distinct type of skiff, is fairly characterized as being a boat for people who really don’t care all that much about boats. They “live” in side yards and driveways, where they are easily available as platforms for fishing, getting out on the water, taking the kids for a boat ride, and just enjoying being out of the house and on the water. Nothing wrong with any of that.

I will leave you with two questions:

What was the pre-industrial precursor/ancestor of the jon boat? Pick a time and place.

Why not build your own simple, practical skiff yourself for the same or less money and the satisfaction of making something with your own hands?

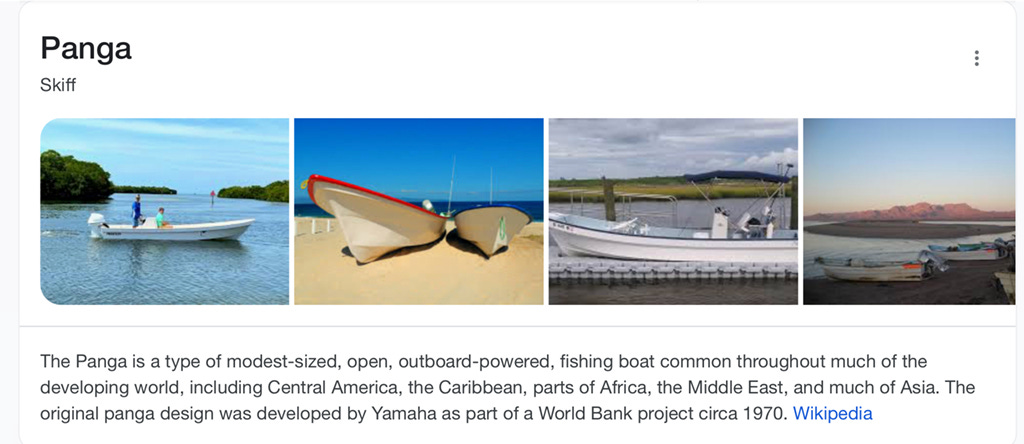

THE PANGA

Several years ago I was in a small town on the coast of the Florida Panhandle at a Fishermen’s Fest one in particular, built of fiberglass in El Salvador and be marketed around Florida. She was attractive: clean lines, lapstrake hull, V bottom up forward and obviously strongly built.

A complete stranger walked up to her, thumped her topsides as a demonstration of expertise (I had just done the very same thing). Then he said something that I have never forgotten, “Ya know, 2000 Somali pirates can’t be wrong! Where else can you find a simple, strong, low-maintenance hull that you can load down with a big outboard, water containers, food, two barrels of gasoline, 8 or 10 guys with weapons and ammo, launch her off the beach through the surf and out into the shipping lanes, waiting days for the right container ship or tanker to come along?”

That boat was a Panga.

The story—there is more than one version—about the origin of the Panga says that in the early 1970s Yamaha got together with the World Bank to design and produce (I’m guessing under license to private companies) a new type of fiberglass boat for use in artisanal fisheries all around the planet. One of the design criteria, not surprisingly, was that the boat be big enough and stout enough to be propelled by a 40HP outboard motor built and sold—all around the planet.

And so the Panga design was born. It’s a good design; cheap to manufacture, burdensome, simple and strong. It can be run up onto a beach and can be launched through the surf. They are all fiberglass, built using a simple mould, and they are found all around the planet. A 2017 article in Boating magazine suggests that the Panga was the solution to the problem of artisanal fishermen needing to go “farther and faster” offshore in order to catch more fish and bring them to market. That may well have the case—I was elsewhere in the early 1970s and I was not thinking about artisanal fisheries. However, I do think about them now and, not surprisingly, I have a different perspective than Boating magazine.

CAUSE AND EFFECT

Mexico, where there are now tens of thousands of Pangas, has coast lines on two oceans, three if you include the Sea of Cortez. Consequently Mexico has a lot of fishing cooperatives.

Q. Was the Panga Project, which Boating states began in Mexico, started by requests from fishing cooperatives on behalf of their members, asking for a new type of boat? i.e., from the bottom up?

Q. If so , how did the fishermen define the problem?

Q. Top Down—How much did the “suits” at the World Bank, and at Yamaha—know about fishing, fish population dynamics, and about fishery regulations aimed at maintaining sustainability?

Q. How much did they know about the boats used in the artisanal fishery?

Q. Was an attempt made to discover “Ground Truth”?

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

1. The invention and widespread acceptance of the Panga resulted in the almost total extinction of regional. traditional boat types, in Mexica and in many other countries as well.

Mexico is a large country with many regions, both geographical and cultural. The traditions of these many regions are made manifest in food, music, dance, ceramics, clothing, language and sports, especially soccer teams. All of these traditions are kept vibrantly alive in 21st century Mexico because they are an important part of national identity and pride, and also because they are powerful advertising tools for the promotion of tourism, which is an important part of the Mexican economy.

It is highly probable that there were small, traditional, regional fishing boats that reflected, as boats do, all around the planet, the history, resource base and economies of the various regions. (Probably not including Chihuahua.) If so, those boats and the people who built and used them to earn a living are now completely gone—casualties of industrialized, homogenized fiberglass construction and the Siren song of the outboard motor.

2. FISHERIES COLLAPSE

Going “farther and faster” offshore sounds like a possible “solution”

Q. What was the “problem”?

It would be interesting to know what percentage of the annual fishing harvest in Mexico stays in Mexico and how much is exported to China—or anywhere else.

To understand the ‘thinking,’ maybe ‘motive’ is a better term, behind both the creation of the Panga and its wide acceptance, it would be helpful to know if a problem was ever articulated, and if so, held up to the light of rational analysis, A.K.A. critical thinking.

More intense fishing meaning going farther and faster, leads to a bigger catch. A bigger catch, over time, causes fish stocks, meaning the fish population, to be depleted. Depleted fish stocks inevitably cause the fishery to collapse. This basic cause and effect sequence has been with us for centuries, in many countries. Connect the dots of going farther and faster with the dots of a bigger hull and a powerful outboard motor and it all starts to look like another case of unintended consequences.

3. ADAPTATION

The growth of tourism in Mexico appears to have given the Panga a new purpose. It is used for whale watching, transporting divers and their heavy equipment, harbor cruises and inshore scientific oceanographic expeditions. The Panga is a useful, practical vessel for these purposes.

Mentioned in the Boating magazine article is a tourism business in La Paz, Baja California, that has three Pangas, each with a 200 H.P. outboard. This, for me, raises another question:In the era of eco-tourism and growing concerns over ocean pollution and the effects of CO2 on climate, how fast do you need to go in your Panga? What might the alternatives be?

All these problems and questions are important, difficult and complex. The events that precipitated them are not unique but they are at least 40 years in the past. Regrettably, their consequences are still with us today.

In summary, let me clearly state that I am not opposed to fiberglass boats and outboard motors. I consider them to be unavoidable and, at certain times, useful. I also think that they, like many other things, are symptoms of real problems, fads and the uncritical acceptance of technologies who’s very real downsides may well have been foreseeable and predictable-had they been thought through more carefully.

For example, outboards, especially four strokes, can be very useful and now have an environmentally “friendly” aspect. Huge, outboards, and multiple huge outboards lined up on the transom of one boat are almost always loud, intrusive and un-seamanlike. They are monuments to male ego, unnecessary and embarrassing. Just how loudly must you proclaim your own wonderfulness?

Fiberglass, when used in boat building, can be very useful. Fiberglass cloth, combined with epoxy resin, is especially useful. But fiberglass is not the answer to all needs. It can degrade,”oil can” and delaminate. Unless it is esthetically “softened” by wooden trim fiberglass can make the interior of boats feel like the interior of a YETI cooler. Fiberglass, unlike wood, is not organic, does not grow from the earth, is not good insulation and is clearly not sustainable. It is difficult to shape with hand tools and unhealthy to breath. Finally, again unlike wood, you can’t put fiberglass scraps in the woodstove to heat the shop on a cold day.

Do not overlook the utility, beauty and practicality of wood.

FELIZ NAVIDAD! HAPPY HANNUKA!

Duncan Blair

As always all opinions expressed above are mine alone. [Except for the guy from the boat show in Florida.]

If you find yourself curious, outraged or interested after reading this post please feel free to contact me at: traditionalsail@gmail.com

Subscriptions are greatly appreciated.

Very interesting!! This mimics many of man’s decisions for “progress” that throws nature out of balance and erases important traditional cultural traditions. Colonizing?? Especially with the world wide goal for distribution - very arrogant to think one boat can replace and improve over centuries of local ingenuity adapted to that specific environment. Also, this Panga idea smacks of the “solutions” for environmental issues that often introduce non-native species to the detriment of the delicate eco web balance! Keep writing! Love your brain!!