Butt Head Schooners and Laguna Madre Scow Sloops

The iconography of contemporary Texas contains the following images: the Alamo, a Lone Star, bar-b-que, (especially brisket), cowboys and Longhorn cattle. Every Texan has these images imprinted in their brain at an early age, and that’s fine, no different from hot rods, surf boards, the Hollywood sign and the Golden Gate bridge for Californians.

Unfortunately, the current Texas iconography lacks one important historical image of something that was an integral part of Texas history for more than 100 years. This is the image of a two-masted, bald-headed (no top sails), gaff-rigged, centerboard schooner, called, not surprisingly, a butt head schooner. It’s Texas.

Why butt head? Because they were scow schooners, with shallow draft and a blunt, transom-like bow that gave greater buoyancy forward for heavy cargo and enabled them to run up onto beaches, sand bars, river banks and marsh grass. A blunt bow, a “pug nose” (see Photo 3 below). Similar scow work boats used to haul building stone in Massachusetts Bay were called “square toe frigates”.

The Texas scow schooners were plain, simple and stout. They were work horses that formed an important part of the economy of rural Texas, which is to say most of Texas. They carried people, livestock and cargo; cotton bales and corn shipped down river from the farms in the interior. They carried cargo to and from sea-going ships anchored off-shore whose draft did not allow them to cross the sand bars at the entrances to the very large and very shallow embayments all along the Texas Gulf coast.

It has always been the case that local conditions of water depth, currents, winds and tides directly effect the hull design and rig of boats working in the local waters.

Most of the settlers who came to Texas in the 1820s and 1830s came from the Southeastern United States; Georgia, Virginia and the Carolinas, all places where large rivers were used by boats, barges and scows to haul agricultural products to the coast. The Texas coast along the Gulf of Mexico, sometimes called America’s Sea, offered similar conditions.

The settlers brought their experience and skill sets with them as intellectual property—the evolution of the scow schooner was one result.

Perfectly fitted to the environment and needs of the Texas economy, the Texas scow schooners continued to be used well into the late 19th century and early 20th century—in spite of the coming of steam power. The schooners were what coastal dwellers understood and were accustomed to and they didn’t have expensive machinery and boilers that could break down or blow up.

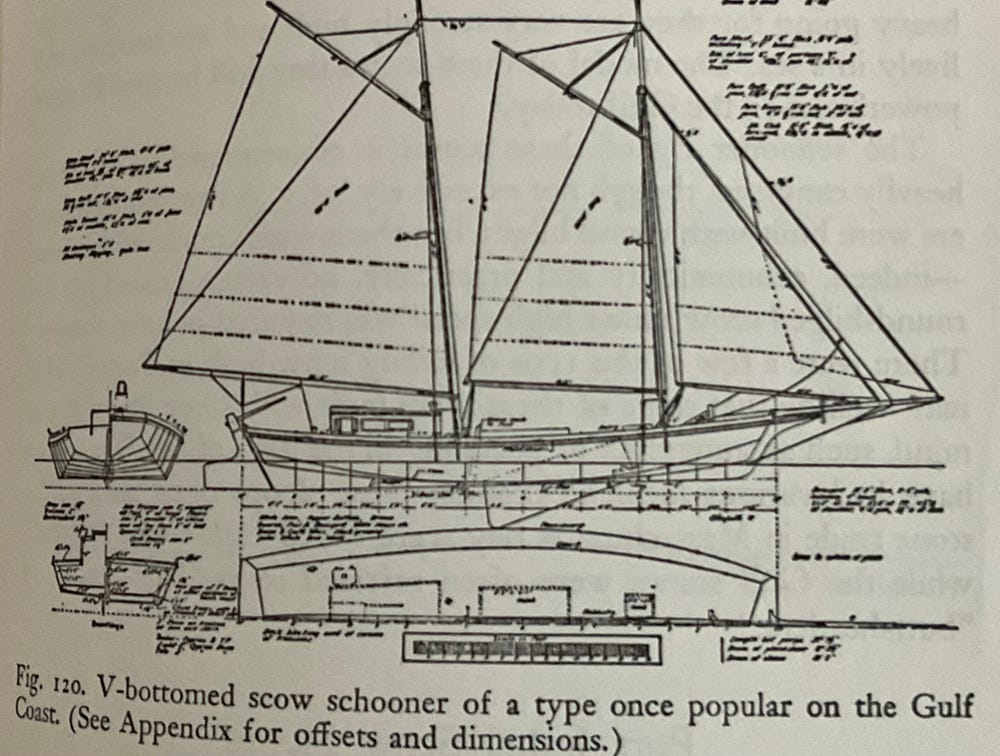

In 1941 Howard Chapelle, a well-known and respected American naval architect and maritime historian, took the lines (meaning carefully measured and recorded the dimensions) of the derelict hull of a scow schooner lying on a beach in Galveston, Texas (see Fig. 1 above).

Chapelle’s book, American Small Sailing Craft, has a section on scow schooners, specifically those in Texas, and presents the dimensions and table of offsets for the one he measured in Galveston. He describes the schooners as being between 32 and 50 feet long, being fast and cheaply built from local materials. As schooners, they also went to windward well and required only a small crew.

The schooner shown in Fig. 1 has a length of 37 feet—between perpendiculars and a beam of about 12 or 15 feet. This is not clear because Chapelle’s numbers and notations are extremely small and difficult to read. You can find them for yourself in American Small Sailing Craft, pg.333, Fig. 120.

Photo #1, seen above, shows a heavily laden Texas scow schooner under way on a beam reach. The cargo is stacked high enough on deck to conflict with the booms if she needs to tack, so hopefully it was a beam reach all the way. This is, to me, is a useful example of how things got done using traditional sail. These guys were not fooling around!

Photo #2 , seen above, shows two scow schooners in the waters off Port Lavaca, Texas. The first, in the foreground, is heavily loaded with party-goers (Today’s Coast Guard would not approve ).

Look closely at the upward curve of the tiller, just as it is shown in Chapelle’s drawing.

The second schooner, in the middle distance and to Port of the party boat, appears to be at anchor, its sails furled and the mainsail boom resting on a boom crutch, bows pointing into the wind—the same wind the party boat is reaching across. The proportions of the deck house, cockpit and forward deck space on the anchored schooner all coincide with Chapelle’s drawing.

Photo #3 above was taken several years ago. It shows the signature pug-nosed, bluff bow of a somewhat controversial scow schooner (See Summary and Questions below) currently in Port Aransas, Texas. She is a replica whose keel was laid, I believe, in 2008.She has long since changed hands, has been partially rebuilt and is not yet complete.

This photo, unlike the first two photos, clearly shows the typical butt head bow, gracefully tapering in from the beam but not so much as to create the typical, conventional fine entry stem piece associated with schooners.

Let’s look at three aspects of this photo, again using Chapelle’s line drawing for comparison.

The skeg—running aft from the bottom of the bow to blend into the keel. I believe that the purpose of the skeg is to “grab” the water as it flows under the bow, thereby providing some directional stability, just like a conventional stem.

2 and 3 (combined); The curved cutwater and the bowsprit. These are both shown in the line drawings but do not appear in the photo because they have yet to be installed or even built.

The cutwater, the curved piece under the bowsprit and up against the bow, is more than decorative. It reinforces and protects the wide planks of the bow, it supports the bowsprit for about 30% of its outboard length and provides a strong point of attachment for the bobstay without creating a hole in the cross planking of the bow.

LAGUNA MADRE SCOW SLOOPS

The Texas Gulf coast is just over 400 miles long. Most of it is protected from the Gulf of Mexico by a string of long, narrow barrier islands, many of the 10 to 15 miles offshore. They run from East to South West. The lower part of the coastline is a shallow protected bay known as the Laguna Madre, starting at Rock Port and running down South West to Port Isabel and Matamoros, where the Rio Grande river reaches the Gulf, where Texas ends and where Mexico begins.

After a stretch of marshlands just South of Matamoros the Laguna Madre begins again, extending further South along the coast of the Mexican state of Tamaulipas for another 150 miles, all of it protected by barrier islands.

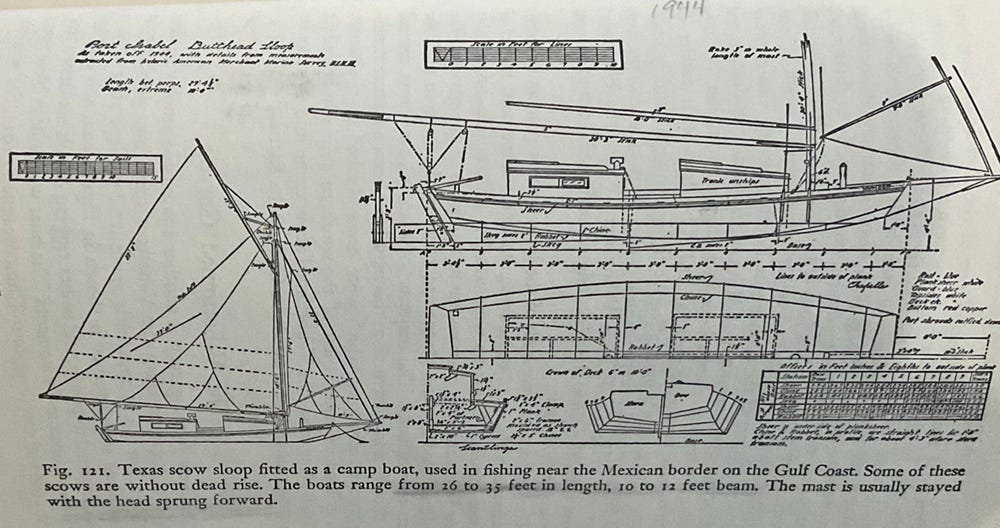

The waters of the Laguna Madre, on both sides of the Texas-Mexico border were the home of the Laguna Madre scow sloop, also called the Port Isabel scow sloop, also measured, written about and admired by Howard Chapelle and also, inevitably, a butt head.

Remember, a schooner has at least two masts but a sloop, any sloop, has only one mast and is almost always smaller than a schooner.

Fig 2 above is a detailed Chapelle drawing of a scow sloop made in 1944 and also published in American Small Sailing Craft. She is smaller than the scow schooner; 29 feet long and 10 feet beam.

She has two sails; a large gaff main sail and a smaller jib with a light weight sprit, allowing the jib to be self-tending.

Unlike the schooner the sloop has two deck houses, the forward being removable so as to make room for extra crew members.

Finally, the Port Isabel sloop has 4 other important features:

Her centerboard is 8 feet long and because it works in concert with the very large mainsail, in order to provide the necessary lateral resistance in extremely shoal water, the surface of the CB when lowered is diagonal, never dropping even close to the vertica—shallow but effective because it is so long.

She has a very large mainsail. (See Photo 4 below)

She carries Lazy Jacks—the network of diagonal lines on both sides of both sails that provides a handy, basket-like containment for the sails when they are lowered, keeping the sails from falling into the water, and temporarily out to the way of the crew. Gaff rig historians say that Lazy Jacks are an American invention.

She has, like most or all Scow Sloops, what Chapelle calls a “drop-blade rudder.” Today these are still seen on other small boat types and are called folding or pop-up rudders.

Chapelle characterizes them as “a most effective fitting, though crudely made.”

In Texas this approach is known as “ Gitter Done!”

The drop blade is a clever, practical adaptation to the very shoal waters of the Laguna Madre and does great credit to its Mexican inventors and fabricators.

Just how these scow sloops came onto the workboat scene in such an isolated location as the Laguna Madre is an excellent example of the confluence of the Natural World, humans, boats and money.

They did not haul cargo like the scow schooners—the interior, up-river landform was and still is Chihuahuan desert; hot, desolate and rocky.

The scow sloops were all about fishing, using gill nets deployed and pulled through the water between two sloops. This is where the big, powerful mainsail came into play.

The Laguna Madre, like most of coastal Texas, is composed of a series of estuaries.

Estuaries are rich in nutrients coming from rivers that flow into them, in this case the Rio Grande, before it was dammed and depleted by the demands of irrigation. Nutrient-rich waters attract and sustain large fish populations.

In the late 19th century the Rio Grande Railroad built a line into Port Isabel, bringing with it a game-changing technology; cheap, transportable ice, in bulk.

So, fish, ice, railroad, markets and people—the only thing missing was boats.

Given the nature of humans and their relationship with boats it is highly probable that there were already gaff sloops on Port Isabel before the railroad arrived, engaging in artisanal, subsistence fishing in both Texas and Mexico. It is also probable that these boats would evolve into the scow sloops bringing innovations like larger sails, self-tending jibs, lazy jacks and drop-blade rudders. This is clearly speculation on my part, but I have spent many years living and working with Mexican working men, so I offer the speculation with confidence.

Railroads, ice, humans, markets for fresh chilled fish in the cities served by the railroads and boats built to catch the fish—using the power of the wind in their sails.

That is one definition of maritime commerce, Marine museums please take note.

Today in Rock Port Texas, at the Eastern limit of the Laguna Madre, there is a 22 foot long replica of a Port Isabel scow sloop at the Texas Maritime Museum. She was built in 1990 by a man named Garza who, I suspect, has since “crossed the bar”. En paz descansa.

The Texas Maritime Museum is the official maritime museum of the State of Texas. Its logo is a stylized drawing of a scow sloop.

The sloop Sr. Garza built is named La Tortuga. She is painted bright red and she sits outside the museum building under a roof, on a concrete slab surrounded by a chain link fence—without any signage or acknowledgement of what she is, why she might be important or why she is there.

She looks beat up, lonely and neglected.

SUMMARY and QUESTIONS

The scow schooner in Port Aransas is named the Lydia Ann. The scow sloop in Rock Port, as mentioned above, is named La Tortuga. If these two boats had voices they might well be singing “Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child”.

Both of these vessel types were still working in the early years of the 20th century—in Texas.

Both of these vessels are owned by organizations dedicated to maritime history and preservation—in Texas.

The schooner is owned by the Port Aransas Preservation and Historical Association-PAPHA.

The sloop, as stated above, is owned by the Texas Maritime Museum (TMM).

Just how are we to understand the mixed messages, the disconnect and the neglect exhibited by these organizations?

If the scow sloop is worthy of being the image on the logo of TMM why isn’t she better preserved, better presented, better honored and explained?

Why isn’t there a replica of a scow sloop, a “piece of living history, ” sailing the waters of Rock Port carrying members of the public and their delighted children?

As for PAPHA, if the scow schooner was thought to be important enough to acquire when her original owner went broke why has she been sitting in a small boat yard, owned by PAPHA, for the last 9 years, without being finished, rigged, launched with great ceremony, and SAILED?

Both of these organizations have professional managers, presidents, boards of directors and donors. I assume that both are making grant applications to fund their activities—on behalf of the citizens of Texas.

It is also a safe bet that they have, or should have, goal statements. I know TMM does because they are on its website.

So, for the last time, these Texas maritime history organizations have dedicated leadership, administration, budgets, goals, policies, funding efforts and physical presence in waterfront communities on the Texas coast.

Given all this, why is it that the two boat types, modest but historically important, are not moving ahead, not being promoted, so as to bring them to the attention—of Texans?

I fully understand that this sorry state of affairs is by no means unique to TMM or PAPHA. I have no doubt that there all sorts of excuses, reasons, justifications and rationalizations that can be offered to the questions above. And I have no doubt that some of those responses may be legitimate—within the context of the organizations.

It is that context, the paradigm, the contextual framework of the organizations, that I take issue with.

What Say You?

Finally, here she is—a photo of a Port Isabel Scow Sloop in her working clothes. The diagonal line with 2 pieces of baggy wrinkle that runs 2 o’clock to 7 o’clock, right to left, is not part of the sloop, nor is the horizontal spar it is connected to. Ignore them.

Do not ignore the signature up-angled tiller or the considerable power of the multiple purchase of the main sheet—necessary due to the power of the sail. Also take note of the fact that she has three rows of reef points.

The condition of the boat and the clothes of the 3 men aboard of her tell us what she and they do for a living.

This, amigos, is TEXAS WORKING SAIL!

Adios,

Duncan Blair

As always, all opinions and ideas expressed above are mine alone.

If this caught your imagination or you eye, feel free to contact me.